Effect of Extremely Low Birth Weight Babies on the Family and Community

- Research

- Open Admission

- Published:

The bear on of preterm birth <37 weeks on parents and families: a cantankerous-exclusive report in the 2 years subsequently discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit

Wellness and Quality of Life Outcomes volume 15, Commodity number:38 (2017) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Little is known about the quality of life of parents and families of preterm infants subsequently belch from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Our aims were (1) to depict the impact of preterm birth on parents and families and (2) and to identify potentially modifiable determinants of parent and family impact.

Methods

We surveyed 196 parents of preterm infants <24 months corrected age in 3 specialty clinics (82% response rate). Principal outcomes were: (one) the Impact on Family unit Calibration total score; and (2) the Baby Toddler Quality of Life parent emotion and (three) time limitations scores. Potentially modifiable factors were utilise of community-based services, financial burdens, and health-related social problems. We estimated associations of potentially modifiable factors with outcomes, adjusting for socio-demographic and infant characteristics using linear regression.

Results

Median (inter-quartile range) babe gestational historic period was 28 (26–31) weeks. Higher Impact on Family scores (indicating worse effects on family functioning) were associated with taking ≥3 unpaid hours/week off from work, increased debt, financial worry, dangerous home environment and social isolation. Lower parent emotion scores (indicating greater impact on the parent) were also associated with social isolation and unpaid fourth dimension off from work. Lower parent fourth dimension limitations scores were associated with social isolation, unpaid time off from work, financial worry, and an unsafe home environment. In dissimilarity, higher parent fourth dimension limitations scores (indicating less impact) were associated with enrollment in early intervention and Medicaid.

Conclusions

Interventions to reduce social isolation, lessen financial burden, amend habitation safe, and increase enrollment in early intervention and Medicaid all have the potential to lessen the bear upon of preterm birth on parents and families.

Background

In the United States, virtually 500,000 infants, or 11.7% of all alive births, are born preterm (<37 weeks' gestation) each twelvemonth [1, 2]. Preterm birth and the sometimes associated prolonged newborn hospitalization are swell family stressors, and tin lead to subsequent family dysfunction [iii–5].

All preterm infants are at hazard for re-hospitalization, besides every bit medical and neurodevelopmental complications, fifty-fifty moderate to late preterm infants (born at 32 to <37 weeks' gestation) [half dozen]. A particularly challenged sub-group is very low nascence weight (VLBW) infants or those built-in < 1500 g. More than ninety% of VLBW infants are discharged home from the neonatal intensive intendance unit (NICU). The burden of connected health and developmental problems faced by these infants is substantial [7–9]. For example, compared with normal nativity weight children, VLBW children face a two–3 fold greater risk for visual and hearing damage, speech delays and attention disorders [10, 11]; may take poor feeding and growth, respiratory complications, and face neurocognitive difficulties [12–16].

Given these ongoing bug and risks, families of preterm children often must manage numerous medical and developmental needs to a higher place and beyond what is required for a healthy full term infant, for months or even years after the neonatal belch. For example, during the offset year of life, VLBW infants are prone to re-hospitalization and crave increased outpatient care [17–xix]. Parents must ship their child for medical appointments and therapies, communicate with the kid'south pediatrician and other healthcare providers, and are often responsible for daily tasks, such as administering medications and monitoring chronic conditions.

The intensity of care and loftier level of vigilance required by families to meet the needs of their preterm child makes it likely that having a preterm child adversely affects the quality of life of the parents and the family overall. The 2006 Institute of Medicine's (IOM) report on Preterm Nascence: Causes, Consequences and Prevention stressed the importance of assessing aspects of family and parent quality of life and stress beyond maternal psychological well-beingness [20–22]. A better agreement of the bear upon of preterm birth on parent and family quality of life, as well equally modifiable factors that predispose parents and families to greater or lesser impact would inform community-based and other structured assistance programs designed to lessen the bear on.

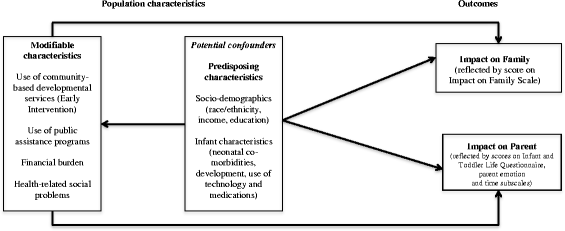

Our main inquiry question was, "Are modifiable characteristics (such as the use of community based and public assist programs, fiscal burden, and health related social issues) associated with the touch of preterm birth on parents and families after NICU discharge?" The Anderson and Aday health utilization model [23, 24] provides a useful framework for addressing our research question because information technology uniquely captures the constructs of access, need, and quality of life. Equally presented in Fig. ane, we conceptualized potentially modifiable characteristics that influence parent and family impact every bit: (1) use of customs based developmental services and public assistance programs; (2) fiscal burden; (3) wellness related social problems. We also specified predisposing characteristics (including socio-demographics and babe wellness characteristics) related both to modifiable characteristics and to outcomes that could human action equally confounders.

Conceptual Model. Adjusted from Phillips [74]

Our specific aims were (1) to describe the touch on of preterm nascency on parents and families and (2) and to identify potentially modifiable determinants of parent and family unit impact. Specific variables of interest based on previous literature, were utilize of customs-based resource, financial burden and wellness-related social problems [25].

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a cantankerous-sectional study. We enrolled one parent (female parent or father) of preterm (<37 weeks gestation) infants attending three outpatient clinics at a large 3rd children's hospital. One clinic provides multidisciplinary medical and neurodevelopmental follow-up for infants with gestational age <32 completed weeks or birth weight <1500 m discharged from i of 3 large, academic NICU'south and affiliated customs-based Level II nurseries, and for more than mature or heavier preterm infants with astringent medical conditions and/or social risk factors (101 participants enrolled). The second clinic provides pediatric pulmonary care for infants with lung disease that originates in the newborn menses, predominantly bronchopulmonary dysplasia (57 participants enrolled). The third dispensary provides follow-up care for infants who have suffered neurologic injury during the fetal or newborn period (38 participants enrolled). While some patients were seen at more than 1 dispensary, they were only enrolled in one case in the written report.

We included parents of preterm infants who were up to 24 months corrected age (historic period from term equivalent). Parents must have been able to answer questions in English or Spanish. If the babe was a multiple, merely i response was collected from the family. Study staff provided eligible families with a letter describing the study. Consent was obtained when the parent agreed to consummate the questionnaire, which was administered on a laptop (with privacy screens) in the clinic waiting room or test room. Participants were provided a small incentive to complete the survey.

The Boston Children's Hospital and Children's Hospital Los Angeles human subjects committees approved the report protocol. Approximately 75% of preterm infants are referred to loftier-risk infant follow upwards programs. [three] In this report, of the 239 eligible participants from Oct, 2011 to June, 2012, 196 completed the questionnaire (82% response rate). The questionnaire is available as Additional file i.

Measurements

Measurements of primary outcomes, modifiable characteristics and potential confounders (predisposing characteristics) are summarized in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Impact on family

The Touch on Family (IOF) [26–28] measures the global impact of pediatric inability on the family and has been validated on samples of children with chronic health conditions, including preterm nativity [25]. The IOF full score is derived from a 27-particular questionnaire. For each item, parents indicate the extent to which they agree with a argument regarding the negative impact of the child on the family unit. Anchors for a 4-point Likert scale were: strongly hold; concord; disagree; and strongly disagree. Examples of IOF items are: "The illness is causing financial problems for the family" and "Our family gives up things because of disease." IOF subscales include financial impact (eight points), disruption of planning (xx points), caretaker brunt (12 points), and familial burden (sixteen points) for total possible score of 56 points. The total negative impact score served equally our summary measure out of family unit burden (higher scores bespeak greater family burden).

In a previous report, internal consistency was high for the overall IOF Scale (Cronbach alphas for full impact, 0.83 to 0.89), but lower for financial (0.68 to 0.79) and coping (0.46 to .52) items [26]. High full scores on the IOF are associated with maternal psychiatric symptoms, poor child health, poor child aligning, increased child hospitalizations, lower maternal pedagogy, and maternal receipt of public assistance [27–29], providing evidence for construct validity.

Impact on parent

The Infant Toddler Quality of Life Questionnaire™ (ITQOL) was developed in 1994 for use in children from 2 months to v years of age as a "profile measure" for health status and health-related quality of life. ITQOL adopts equally its conceptual framework the Earth Health Organization's definition of health as a state of consummate physical, mental and social well-being and non just the absence of illness [30]. It has been used both in randomized clinical trials [31] and observational studies, and is accepted favorably for its ease of employ and understandability [32].

In this study, nosotros used the Family unit Burden scales of the ITQOL, which embrace 2 parent-focused concept subscales, impact-emotion and touch on-time, due to caring for their infant or toddler [30, 32, 33]. The parent bear on-emotion domain consists of 7 items in which the parent is asked to rate how much anxiety or worry each of the kid characteristics described in the items has acquired during the past 4 weeks (i.due east., feeding/sleeping/eating habits; concrete health, emotional well being, learning abilities, ability to interact with others; behavior and temperament). The parent touch on-time domain consists of seven items in which the parents is asked to rate how much of his/her time was express for personal needs because of the issues with the child'south personal needs during the past 4 weeks. Internal consistency for the ITQOL parent-touch on emotion and parent-impact fourth dimension scales has been reported in three different populations, a Dutch general population sample (0.61, 0.64) [34], a functional abdominal hurting sample (0.72, 0.73) [35] and a burn injury sample (0.79, 0.84) [xxx, 36].

Raw subscale scores are converted to standardized scores on a 0–100 continuum [37–40]. For each scale, college scores indicate less emotional impact and fewer time limitations on the parent (in other words, college scores stand for more than favorable outcomes).

Potentially modifiable characteristics

Apply of community-based resources

Participants were asked yes/no questions about the use of community-based developmental resource (such equally early intervention programs), use of social services such as food assist programs, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme and the Women, Infant, Children's programme also as energy assist/disability programs such the Low Income Dwelling house Energy Assist Plan, Transitional Aid to Families with Dependent Children, and receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

Financial Burden

In add-on to questions most employment for the participating parent and his/her partner, we asked half-dozen yes/no questions from the 2007 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Wellness Insurance Survey [41–44] regarding unexpected costs, increased bills, increased out-of-pocket expenses and financial worry.

Health-related social bug

HelpSteps.com is a survey designed to place health-related social problems. Evolution of HelpSteps involved literature review and fundamental informant interviews with wellness and social services experts, yielding an initial listing of 25 social domains. Of those, the 5 most relevant domains were identified using a modified Delphi technique: (1) access to health care, (2) housing, (3) food security (4) income security and (five) intimate partner violence [45–48]. About questions about these domains were adapted from previous surveys (e.thou. National Health Interview Survey [49], the American Housing Survey [50], the Philadelphia Survey of Work and Family [51] and the Childhood Community Hunger Identification Project [52]), while a few newly written items were too incorporated into the concluding HelpSteps survey. In terms of content validity, the domains covered in HealthSteps are well-recognized equally being closely tied to health outcomes and costs [53]. HelpSteps is highly constructive in identifying issues that can be addressed by referral to advisable social services [46, 47] and a qualitative study revealed that over 2/3 of participants constitute the HealthSteps questions to be highly relevant to their own bug [48].

Predisposing characteristics (potential confounders)

Infant wellness and development

We obtained data from the medical record regarding delivery and complications during the neonatal hospitalization. Nosotros asked parents questions about their babe's health status since discharge including the number of emergency department visits, monthly clinic appointments, and hospitalizations, immunizations, dependence on engineering, and administration of prescription medications.

To assess baby development, nosotros used the Motor and Social Development (MSD) scale [54], which was developed by the National Centre for Health Statistics to mensurate motor, social and cerebral development of young children. Of 48 items derived from standard measures of child evolution, including the Bayley Scales, Gesell Scale, and Denver Developmental Screening Test, parents complete 15 historic period-specific items, which ask about specific developmental milestones such equally laughing out loud, pulling to stand, and saying recognizable words [55]. We selected the MSD because it is brief and allows for scoring based on a large, national sample [56] with a normative mean of 100 and standard divergence xv, similar to other developmental tests. College scores point better development. In a previous written report of former preterm infants, we showed that the MSD has good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha 0.65-0.88) and is modestly correlated with Bayley Scales of Baby and Toddler Devleopment, 3rd edition, a aureate standard professionally administered neurodevelopmental test [56]. Another study reported that infants with lower gestational age at birth have lower scores on the MSD [54]. Although the MSD includes a cognitive, motor, and social subscales, the degree to which it is sensitive to language/communication delays is unknown, which is a potential limitation.

Statistical assay

Our main outcomes were: (1) impact on family total score; (2) touch on on parent score determined by the concept of emotion; and (3) touch on parent score determined by the concept of limitation of time. Potentially modifiable determinants included the use of community-based resources, financial burden, and health-related social problems. Potential confounders (predisposing characteristics) were socio-demographics and babe pre-disposing and post-belch characteristics.

In bivariate analyses, we compared effect scores across categories of predisposing characteristics (potential confounders) and potentially modifiable determinants. We calculated p-values using not-parametric tests (Wilcoxon Rank Sum or Kruskal Wallis). To identify potentially modifiable determinants independent of confounders on our chief outcomes, nosotros created parsimonious multivariable models, adjusting for variables of a priori involvement and for other characteristics found to be significant at p <0.1. We likewise examined each model using variance aggrandizement factors (VIF) and did not detect meaning collinearity (VIF ≤ 2 for all models).

We used SAS version ix.four (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for analyses.

Results

Participant characteristics and outcomes

Predisposing characteristics of study participants and outcome measures are shown in Table 1. A majority of participants were white, non-Hispanic (67%). 52% reported an almanac household income of ≥ $eighty,000 and 68% of mothers had attended at least some college. The median (IQR) gestational age of infants at nascency was 28 weeks (26–31). The median (interquartile range, IQR) chronologic historic period of infants at the fourth dimension of report participation was 10.4 months (7.5-17.2).

Unadjusted associations of predisposing characteristics (potential confounders) with outcomes

As shown in Table 1, amongst pre-disposing characteristics, the utilise of medical technology, receipt of at least one prescription medication daily, one or more readmission or emergency section visit after neonatal discharge, and two or more clinic appointments per month were all associated with greater bear on on family, parents, or both. Additionally, having an babe with a depression developmental score (MSD < 85) was associated with greater impact on the family and parent emotion. Fathers who completed the survey had higher impact scores than mothers on the parent-focused domains of emotion and time limitations. Of note when nosotros performed an additional sensitivity analysis by running our multivariate models for mothers only, we plant our multivariate model estimates were similar in magnitude and management as the full models that included fathers.

Potentially modifiable characteristics and unadjusted associations with outcomes

Table 2 shows that use of public housing and public aid programme were associated with greater touch on family. Compensation for fourth dimension taken off from work was associated with a lower parent emotional score (less parental impact) while use of social services, public housing, enrollment in Medicaid and an unsafe home environment were associated with a higher IOF score (greater family impact). Markers of fiscal burden (including unpaid time off work, increased out-of-pocket expenses, bills, debt and financial worry) and social isolation were associated with both greater family and parental impact.

Adjusted associations of potentially modifiable characteristics with outcomes

Table 3 shows associations of potentially modifiable characteristics with the total IOF Scale scores, adjusting for potential confounders. Taking time off from work without pay, increased bills, financial worry, an unsafe dwelling environment, and social isolation were all associated with higher total IOF scores, indicating greater bear upon. Similarly, Tabular array 4 shows adjusted associations of potentially modifiable characteristics with impact on Parent Emotion and Fourth dimension Limitation scores. Taking fourth dimension off from work without pay and social isolation were associated with lower scores on both of these scales, indicating greater impact. Fiscal worry was associated with greater impact on parent time limitation, as was an dangerous home environment. In dissimilarity, enrollment in early intervention and Medicaid programs were associated with higher parent time limitation scores, indicating less parental impact.

Discussion

In this study, we described the impact of preterm nascence on parents and families in the first ii years subsequently neonatal discharge. Our results support our conceptual model, which posits modifiable factors that are associated with the impact of preterm birth on parents and families, independent of infant wellness and socio-demographic characteristics. We identified several potentially modifiable factors that were associated with both higher and lower impact. In particular, social isolation, financial burdens such equally taking unpaid time off from work, increased bills and financial worry, and an unsafe home environment were all associated with college impact on at least i of our main outcomes. In dissimilarity, enrollment in early on intervention and Medicaid and use of public housing were associated with less parent impact.

Predisposing characteristics such equally infant co-morbidities affected both touch on family scores and parental scores. Baby development afflicted parental scores for increased anxiety and emotion. Our findings were consistent with previous studies that the impact was greater amongst families whose preterm children demonstrated either a functional handicap or low developmental quotient [22, 25, 57–59]. We likewise plant that the utilise of prescription medications and durable medical equipment affected both parental impact scores and impact on family scores, which was consistent with other publications [xx, 60]. Specifically, the utilise of medications and medical equipment may contribute to the substantial out-of-pocket expenditures that families may incur [61, 62]. As force per unit area mounts to reduce hospital length of stay and readmission rates, and equally we move more complex care into the customs, high out-of-pocket costs is an of import cistron that tin contribute to parental and family unit strain.

Several studies take shown that preterm birth and an infant's hospitalization can adversely affect the finances of families after the birth of a preterm or VLBW babe [20, lx–63]. Withal, little is known about a more than modifiable determinant such as the specifics of financial brunt faced by families, or near the bear upon of financial burden on parent quality of life. In our report, we institute that a lack of compensation for fourth dimension off work was associated with both family and parent-fourth dimension impact scores. Also, increased bills due to hospitalization and increased financial worry were associated with greater bear upon. Complementing our findings, 2 studies have reported the out-of-pocket costs incurred by families of preterm infants for outpatient services, medications, as well as indirect costs like lost productivity are meaning especially during the beginning yr after discharge [60, 64]. Specifically, Hodek et al. cited that co-payments for outpatient ancillary services and medications increased parental out-of-pocket expenses. Moreover, lost wages for missing work days may increase income losses [60]. Overall, by highlighting the specific aspects of financial burden most closely associated with parent and family unit touch on, such as lack of compensation and increased bills, our results may inform targeted financial back up programs for families of preterm infants later on belch. Moreover, our findings back up that while annual income was not associated with impact on family, parental perspective on financial burden was, which should also exist considered when caring for these families.

Another modifiable determinant are health related social problems. These are economical and social problems that can touch on health such every bit food insecurity and substandard housing [45]. Prior studies have demonstrated the touch of substandard housing on kid wellness such as increased communicable diseases and injury [65]. All the same, nosotros found that an unsafe dwelling environment was associated with adverse parent-fourth dimension impact and impact on the family. Timely receipt of public housing has been associated with improved wellness in other medical condtions [66]. Addressing housing concerns for families of preterm infants through existing public housing programs is a feasible arroyo to reducing the parental and family impact.

Some other health related social problem that was associated with greater parental and family impact was social isolation. Other studies that have examined families of premature infants have plant that "breach" [67] and social isolation may take profound impact on parental emotion [68]. Jackson et al. described the paradigm of the process of acclimatization of caring for a premature infant equally breach, responsibility, confidence and familiarity, and that alienation may be protracted in this population [67]. Intervention strategies that have improved parental emotions ofttimes include pedagogy-behavioral models. For example, the Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) programme created by Melnyk, et al. was associated with reduced parental impact during transition home from the NICU [69, 70]. It is possible that programs like that one benefit families by reducing social isolation in months to years afterwards belch.

Another modifiable determinant is enrollment in a community-based developmental program like "Early Intervention (EI)," was associated with less bear on on parental limitation of fourth dimension. A recent meta-assay suggests that customs-based developmental programs had beneficial pooled effects on maternal anxiety, depressive symptoms, and self-efficacy [71]. Moreover, other studies have suggested that these programs can also empower families because of the collaborative procedure that EI offers; in turn, they have a deeper understanding of their child'due south developmental needs [72].

Similarly to early intervention, we found that receipt of Medicaid was associated with lower bear on scores on limitations on time. Other studies have demonstrated families who were registered with Medicaid showed improved "parent role confidence" and "parent-infant interaction" than those with private insurance [69]. While this result was unexpected, it has been speculated that parents with a higher socioeconomic status and individual insurance may accept college expectations for themselves [69] and therefore may perceive an increased parental impact on their time versus those who utilize Medicaid. Overall, our results suggest that greater participation in public assistance programs may lessen familial and parental burden for this patient population.

A strength of our study was our loftier response rate (82%). Characteristics of the infants were very similar to other follow-upwardly programs [25]. Nevertheless, we studied families of infants presenting for follow-upwardly intendance rather than the underlying population of families of infants receiving neonatal intensive care, potentially limiting generalizability. Moreover, nosotros did sample both mothers and fathers, which may bear on how some of our results are interpreted and parent gender may influence some of the measures including financial burden and social isolation [73]. Also, our study was cantankerous-sectional making us unable to establish causation. While nosotros adapted for a number of potential confounders, similar all observational studies, ours is discipline to residual misreckoning. While nosotros did non have a total term cohort control in comparison [25], nor data on those not enrolled, our aim was to elicit the experience of parents and families of preterm infants, equally well as relationships with modifiable characteristics specific to this population.

Conclusions

In summary, we identified several predictors of increased family and parent impact in families of preterm infants. Of particular involvement were the potentially modifiable factors including social isolation and fiscal brunt, which were associated with greater touch on, and utilize of customs-based developmental services, public housing, and Medicaid which were associated with less impact. Our results suggest that interventions to target these factors, for example social and financial support programs, and efforts to increase enrollment in customs-based developmental services and public health insurance programs, might lessen the touch on of preterm nativity on parents and families.

Abbreviations

- IOF:

-

Affect on family unit full score

- ITQOL:

-

Infant toddler quality of life

- MSD:

-

Motor and social development

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive intendance unit of measurement

- PFB:

-

Perceived financial burden

References

-

Hamilton Be, Hoyert DL, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2010–2011. Pediatrics. 2013;131:548–58.

-

Wang CJ, McGlynn EA, Beck RH, et al. Quality-of-care indicators for the neurodevelopmental follow-upwardly of very depression birth weight children: results of an expert panel procedure. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2080–92.

-

Newborn AAoPCotFa. Hospital discharge of the high-take a chance neonate. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1119–26.

-

Garfield L, Holditch-Davis D, Carter CS, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in low-income women with very depression-birth-weight infants. Adv Neonatal Intendance. 2015;fifteen:E3–eight.

-

Howe TH, Sheu CF, Wang TN, Hsu YW. Parenting stress in families with very depression birth weight preterm infants in early infancy. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35:1748–56.

-

Thygesen SK, Olsen Yard, Ostergaard JR, Sorensen HT. Respiratory distress syndrome in moderately tardily and tardily preterm infants and run a risk of cerebral palsy: a population-based cohort report. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011643.

-

Vohr BR, Wright LL, Dusick AM, et al. Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low nascence weight infants in the National Found of Child Health and Homo Evolution Neonatal Enquiry Network, 1993–1994. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1216–26.

-

Hack M, Taylor HG, Drotar D, et al. Chronic conditions, functional limitations, and special health care needs of school-anile children born with extremely low-nascency-weight in the 1990s. JAMA. 2005;294:318–25.

-

Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371:261–9.

-

McCormick MC, Richardson DK. Premature infants grow upward. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:197–8.

-

Cheung PY, Barrington KJ, Finer NN, Robertson CM. Early babyhood neurodevelopment in very low birth weight infants with predischarge apnea. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;27:14–20.

-

de Kieviet JF, Piek JP, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Oosterlaan J. Motor development in very preterm and very low-birth-weight children from birth to adolescence: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302:2235–42.

-

Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Smidts DP, Oosterlaan J, Duivenvoorden HJ, Weisglas-Kuperus N. Executive function in very preterm children at early on school age. J Abnorm Kid Psychol. 2009;37:981–93.

-

Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus Due north, van Goudoever JB, Oosterlaan J. Meta-assay of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:717–28.

-

de Kieviet JF, Zoetebier L, van Elburg RM, Vermeulen RJ, Oosterlaan J. Brain development of very preterm and very low-birthweight children in babyhood and boyhood: a meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:313–23.

-

Burnett Air conditioning, Scratch SE, Lee KJ, et al. Executive Function in Adolescents Born <1000 thousand or <28 Weeks: A Prospective Cohort Study. Pediatrics 2015.

-

Donohue PK. Wellness-related quality of life of preterm children and their caregivers. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:293–7.

-

Escobar GJ, Joffe S, Gardner MN, Armstrong MA, Folck BF, Carpenter DM. Rehospitalization in the beginning two weeks subsequently discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e2.

-

Joffe South, Escobar GJ, Blackness SB, Armstrong MA, Lieu TA. Rehospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus among premature infants. Pediatrics. 1999;104:894–9.

-

Als H, Behrman R, Checchia P, et al. Preemie abandonment? Multidisciplinary experts consider how to best come across preemies needs at "preterm infants: a collaborative approach to specialized care" roundtable. Mod Healthc. 2007;37:17–24.

-

Behrman RaB, AS. 2007. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press (US); Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention.

-

Cronin CM, Shapiro CR, Casiro OG, Cheang MS. The touch of very low-nascence-weight infants on the family unit is long lasting. A matched control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:151–8.

-

Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;nine:208–20.

-

Raina P, O'Donnell G, Schwellnus H, et al. Caregiving procedure and caregiver brunt: conceptual models to guide research and practice. BMC Pediatr. 2004;4:ane.

-

Drotar D, Hack 1000, Taylor 1000, Schluchter Chiliad, Andreias L, Klein N. The impact of extremely low birth weight on the families of school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2006–thirteen.

-

Jessop DJ, Stein RE. Dubiousness and its relation to the psychological and social correlates of chronic illness in children. Soc Sci Med. 1985;20:993–nine.

-

Stein RE, Jessop DJ. What diagnosis does not tell: the example for a noncategorical arroyo to chronic affliction in childhood. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29:769–78.

-

Stein RE, Jessop DJ. Measuring health variables among Hispanic and non-Hispanic children with chronic conditions. Public Health Rep. 1989;104:377–84.

-

Stein RE, Jessop DJ. The impact on family scale revisited: further psychometric data. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24:nine–16.

-

Landgraf JM, Vogel I, Oostenbrink R, van Baar ME, Raat H. Parent-reported health outcomes in infants/toddlers: measurement backdrop and clinical validity of the ITQOL-SF47. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:635–46.

-

Kruizinga I, Jansen W, van Sprang NC, Carter Equally, Raat H. The Effectiveness of the BITSEA as a Tool to Early Discover Psychosocial Issues in Toddlers, a Cluster Randomized Trial. PLoS 1. 2015;10:e0136488.

-

Flink IJ, Beirens TM, Looman C, et al. Health-related quality of life of infants from indigenous minority groups: the Generation R Study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:653–64.

-

Flink IJ, Prins RG, Mackenbach JJ, et al. Neighborhood ethnic multifariousness and behavioral and emotional problems in iii year olds: results from the Generation R Report. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70070.

-

Raat H, Landgraf JM, Oostenbrink R, Moll HA, Essink-Bot ML. Reliability and validity of the Infant and Toddler Quality of Life Questionnaire (ITQOL) in a general population and respiratory disease sample. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:445–60.

-

Oostenbrink R, Jongman H, Landgraf JM, Raat H, Moll HA. Functional abdominal complaints in pre-schoolhouse children: parental reports of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:363–9.

-

van Baar ME, Essink-Bot ML, Oen IM, et al. Reliability and validity of the Health Outcomes Burn Questionnaire for infants and children in The Netherlands. Burns. 2006;32:357–65.

-

ITQOL: Infant Toddler Quality of Life Questionnaire. (Accessed Dec 2nd, 2016, at healthactchq.com.)

-

Meert KL, Slomine BS, Christensen JR, et al. Family Burden Later on Out-of-Infirmary Cardiac Abort in Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:498–507.

-

van Zellem L, Buysse C, Madderom M, et al. Long-term neuropsychological outcomes in children and adolescents subsequently cardiac abort. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1057–66.

-

Rolfsjord LB, Skjerven HO, Carlsen KH, et al. The severity of acute bronchiolitis in infants was associated with quality of life ix months later. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105:834–41.

-

Doty Grand, Rustgi SD, Schoen C, Collins SR. Maintaining wellness insurance during a recession: likely COBRA eligibility: an updated assay using the Commonwealth Fund 2007 Biennial Health Insurance Survey. Outcome brief. 2009;49:1–12.

-

Doty MM, Collins SR, Nicholson JL, Rustgi SD. Failure to protect: why the individual insurance market place is not a viable option for nearly U.S. families: findings from the Republic Fund Biennial Wellness Insurance Survey. Issue brief. 2009;62:1–16.

-

Doty MM, Collins SR, Rustgi SD, Nicholson JL. Out of options: why so many workers in modest businesses lack affordable health insurance, and how wellness care reform tin can help. Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Wellness Insurance Survey, 2007. Effect brief. 2009;67:1–22.

-

Rustgi SD, Doty MM, Collins SR. Women at hazard: why many women are forgoing needed health care. An analysis of the Democracy Fund 2007 Biennial Wellness Insurance Survey. Result brief. 2009;52:1–12.

-

Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Muret-Wagstaff S. Families' health-related social issues and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1332–41.

-

Hassan A, Blood E, Pikcilingis A, Krull E, McNickles 50, Marmon 1000, Wood E, Fleegler Due east. Improving Social Determinants of Health: Effectiveness of a web-based intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(vi):822-31. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.023.

-

Hassan A, Blood EA, Pikcilingis A, et al. Youths' health-related social issues: concerns oftentimes overlooked during the medical visit. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:265–71.

-

Wylie SA, Hassan A, Krull EG, et al. Assessing and referring adolescents' health-related social problems: qualitative evaluation of a novel web-based approach. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18:392–eight.

-

Statistics NCoH. National Health Interview Survey. Washington DC: Services UDoHaH, ed.; 1995.

-

Bureau UC. The American Housing Survey. Washington DC: Development DoHaU, ed; 1994.

-

Cress JFJ. The Philadelphia Survey of Child Intendance and Work. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University; 2003.

-

Weinreb L, Wehler C, Perloff J, et al. Hunger: its impact on children'due south wellness and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e41.

-

Accountable Health Communities Model. 2016. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/AHCM). Accessed eighteen Dec 2016.

-

Hediger ML, Overpeck MD, Ruan WJ, Troendle JF. Birthweight and gestational age effects on motor and social evolution. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2002;16:33–46.

-

at http://world wide web.nlsinfo.org/childya/nlsdocs/questionnaires/2006/Child2006quex/ MotherSupplement2006_Assessments.html#MOTORANDSOCIALDEVELOPMENT).

-

Belfort MB, Santo East, McCormick MC. Using parent questionnaires to assess neurodevelopment in former preterm infants: a validation study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:199–207.

-

Rivers A, Caron B, Hack M. Experience of families with very low birthweight children with neurologic sequelae. Clin Pediatr. 1987;26:223–xxx.

-

Taylor HG, Klein N, Minich NM, Hack Thou. Long-term family unit outcomes for children with very low nativity weights. Curvation Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:155–61.

-

Saigal Southward, Burrows Due east, Stoskopf BL, Rosenbaum PL, Streiner D. Impact of extreme prematurity on families of adolescent children. J Pediatr. 2000;137:701–half-dozen.

-

Hodek JM, von der Schulenburg JM, Mittendorf T. Measuring economic consequences of preterm nativity - Methodological recommendations for the evaluation of personal burden on children and their caregivers. Heal Econ Rev. 2011;1:6.

-

Petrou S. Economic consequences of preterm birth and low birthweight. BJOG. 2003;110 Suppl 20:17–23.

-

McCormick MC, Bernbaum JC, Eisenberg JM, Kustra SL, Finnegan E. Costs incurred by parents of very low birth weight infants later the initial neonatal hospitalization. Pediatrics. 1991;88:533–41.

-

Underwood MA, Danielsen B, Gilbert WM. Price, causes and rates of rehospitalization of preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2007;27:614–nine.

-

Schiffman JK, Dukhovny D, Mowitz Yard, Kirpalani H, Mao Westward, Roberts R, Nyberg A, Zupancic J. Quantifying the Economic Burden of Neonatal Affliction on Families of Preterm Infants in the U.S. and Canada. San Diego, CA: Pediatric Bookish Societies; 2015.

-

Krieger J, Higgins DL. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:758–68.

-

Rodgers JT, Purnell JQ. Healthcare navigation service in ii-ane-i San Diego: guiding individuals to the intendance they need. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:S450–vi.

-

Jackson M, Ternestedt BM, Schollin J. From alienation to familiarity: experiences of mothers and fathers of preterm infants. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43:120–9.

-

Meijssen DE, Wolf MJ, Koldewijn K, van Wassenaer AG, Kok JH, van Baar AL. Parenting stress in mothers afterward very preterm birth and the result of the Infant Behavioural Assessment and Intervention Plan. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:195–202.

-

Melnyk BM, Oswalt KL, Sidora-Arcoleo K. Validation and psychometric backdrop of the neonatal intensive care unit parental behavior calibration. Nurs Res. 2014;63:105–15.

-

Melnyk BM, Alpert-Gillis LJ. The COPE program: a strategy to improve outcomes of critically sick young children and their parents. Pediatr Nurs. 1998;24:521–7.

-

Benzies KM, Magill-Evans JE, Hayden KA, Ballantyne M. Key components of early intervention programs for preterm infants and their parents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13 Suppl one:S10.

-

Pighini MJ, Goelman H, Buchanan M, Schonert-Reichl K, Brynelsen D. Learning from parents' stories near what works in early on intervention. Int J Psychol. 2014;49:263–70.

-

Arockiasamy V, Holsti L, Albersheim S. Fathers' experiences in the neonatal intensive intendance unit: a search for command. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e215–22.

-

Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Anderson R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: Assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Wellness Serv Res. 1998;33:571–96.

Acknowledgments

This report was supported by the Richardson Fund, Department of Neonatology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston MA, the Program for Patient Condom and Quality (PPSQ) at Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA and the Medical Staff Organization at Boston Children's Infirmary, Boston, MA.

Nosotros would similar to thank the families who participated in this written report. We would besides like to recognize Jane Stewart, Physician, the managing director of the Babe Follow Up Program (IFUP) at Boston Children'southward Hospital, Larry Rhein, MD, the director of the Middle for Salubrious Infant Lung Development (Child) program at Boston Children'due south Infirmary and Janet Soul, MD, the managing director of the Fetal Neurology Plan at Boston Children's Hospital who facilitated our study. Nosotros would also like thank Brooke Corder, the social worker at the IFUP who assisted with patient recruitment. Nosotros would besides like to admit Aaron Picklingis who developed the web-interface for the written report questionnaire and Drs. Dionne Graham and Sheree Schrager who assisted with statistical analysis.

Funding

This study was likewise supported by the Richardson Fund with the Department of Neonatology, Beth State of israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston MA, the Program for Patient Safety and Quality (PPSQ) at Boston Children'south Hospital, Boston, MA and the Medical Staff Organization at Boston Children'due south Hospital, Boston, MA.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the electric current study are not publicly available due to patient data, just are bachelor from the respective writer on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

Dr. Lakshmanan and Dr. Belfort fabricated substantial contributions to designing the study, analyzing the data, and interpreting the results. Dr. Lakshmanan wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Ms. Agni collected the data and contributed to data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. Drs. Lieu, Fleegler and McCormick made substantial contributions to designing the written report, interpreting the results, and critically revising the manuscript. Drs. Kipke and Friedlich likewise assisted in interpreting the results and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. There is no identifiable data in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ideals approval and consent

The Boston Children's Hospital and Children's Hospital Los Angeles human being subjects committees approved the study protocol and participation consent was obtained from all subjects.

Financial disclosure

Dr. Lakshmanan is supported past National Center for Advancing Translational Scientific discipline (NCATS) of the U.Southward. National Institutes of Wellness (KL2TR001854). Dr. Belfort was supported by National Institutes of Health K23DK83817. The remaining authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Writer information

Affiliations

Respective author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Presurvey information demographics. (DOC 108 kb)

Additional file ii: Table S1.

Description of measurement instruments for main outcomes, modifiable determinants and predisposing characteristics (potential confounders). (DOC 55 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you lot give advisable credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and betoken if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cypher/one.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Lakshmanan, A., Agni, M., Lieu, T. et al. The impact of preterm birth <37 weeks on parents and families: a cross-sectional study in the 2 years later discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15, 38 (2017). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12955-017-0602-three

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12955-017-0602-iii

Keywords

- Affect on family unit

- Impact on parents

- Prematurity

- Loftier-run a risk infant

- Post-discharge

Source: https://hqlo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12955-017-0602-3

0 Response to "Effect of Extremely Low Birth Weight Babies on the Family and Community"

Post a Comment